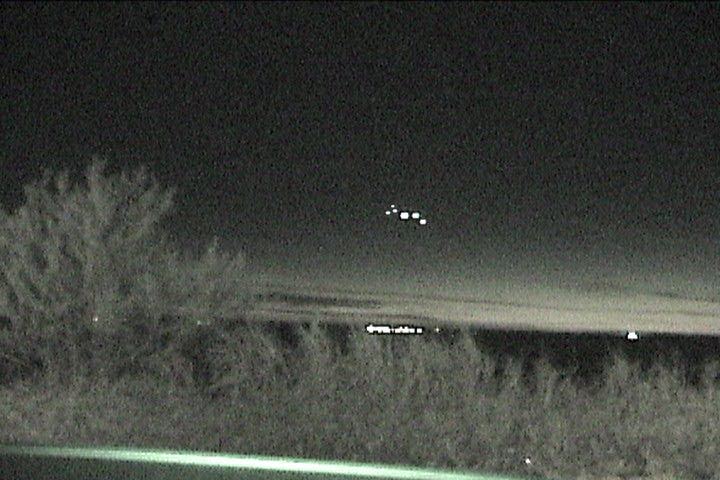

A child walks on a

makeshift bridge between shanty homes built on top of banks of tombs

inside the north Manila cemetery. Photograph: Noel Celis/AFP/Getty

Images

Every morning, Alberto Lagarda Evangelista, 71, leaves the

two-storey, lemon-yellow home he has lived in for the past decade and

walks to work at the cemetery next door. As a caretaker of about 20

graves, Evangelista earns just 20,000 pesos (£315) a year, a sum so

small that he must share his house with seven other people – all of whom

are dead.

Evangelista lives and works in the Cementerio del

Norte, a sprawling, 54-hectare green space in north Manila that is also

home to some 1,000 other families. Here in the

Philippines'

largest public graveyard, century-old tombs have been converted into

stalls selling sachets of shampoo and instant noodles, clothes lines are

strung between crosses and car batteries power radios, karaoke machines

and television sets. Evangelista's home is a mausoleum housing eight

graves. The breezy second storey where the owners pay their annual

respects to the dead doubles as his bedroom. "Just look at my view," he

says, pointing his cigarette out towards the grave-studded horizon.

Today,

the shady lanes are busy with the sundry activities of any normal

neighbourhood: a group of boys plays basketball; adults while away the

afternoon heat with sodas and playing cards; couples canoodle atop the

graves that double as their beds; and women prepare chicken

adobo in their mausoleum cafes.

The

cemetery's inhabitants rank among the poorest of the poor in Manila, a

capital where roughly 43% of the city's 13 million residents live in

informal settlements like this one, according to a 2011

Asian Development Bank report.

This Roman Catholic country has one of Asia's fastest growing

populations and a massive housing shortage – meaning that the urban poor

must usually find, build or cobble together housing anywhere there is

space: under bridges, along highways, in alleys, perched atop flood

channels, or even among the dead.

No one knows exactly when the

cemetery became a living village. But many of Manila North's 6,000-odd

residents were born here and expect to spend their whole lives here.

Gravedigger Steve Esbacos, 52, a muscular man with blue-rimmed eyes, was

born and raised in the same mausoleum where he now raises his own four

children. "Sometimes I don't like living here, because it's dirty and it

smells bad," he says, before admitting that he's never wanted to live

anywhere else. "My father is buried just over there and I don't know

where else I'd go."

Ramil and Josephine Raviz run a stall selling

instant noodles and peanuts to residents and mourners. They earn enough

money to send their 10-year-old daughter to school, and say they prefer

life here to the possibilities "outside" the cemetery's four walls.

"When

I first came to Norte 30 years ago, there weren't so many families here

– it was quiet and peaceful and safe, very different to the outside

slums in Manila," says Ramil, 46, in his mausoleum housing a fan,

fridge, rocking chair, microwave, blankets and mattresses, and six

graves. "But once people realised they could work here and live here for

free, they moved in."

The cemetery hasn't retained that peaceful

aura. Robberies and muggings are common, residents admit, with gangs

said to be working different corners of the sprawling greenery. Youth

unemployment is high and alcohol cheap. City authorities have repeatedly

threatened to evict those living here. But grave-dwellers have found a

way to stay on despite the pressure, using ad-hoc "deeds" from the

families whose graves they maintain, allowing them to live and work

on-site.

The issue is not so much people living in the cemetery –

where quarters can be more spacious and cleaner than in a shanty on one

of the city's easily flooded riverways – but the fact that Manila is not

properly addressing the needs of the urban poor, says Father Norberto

Carcellar, director of Philippine Action for Community-Led Shelter

Initiatives. "Poor people can pay as much as four times [the normal

rates] for electricity and water in their shanties because mafia

syndicates take over and they have no choice but to pay [the higher

rates]," he says.

"These people are 'invisible' – they can be

evicted at any time, they face floods, they live on the periphery and

the government generally likes to send them very far away to other

provinces [to deal with the problem]."

Under a $1.2bn (£800m)

government mandate to clean up Manila, that may soon change. Recent

official figures show 104,000 families live in danger areas such as

graveyards and riverbeds, and the city aims to move 550,000 of the most

vulnerable residents to safer destinations. Some will be residents of

Manila North, yet no one in the cemetery seems ready – or willing – to

go.

"I often think, what would have happened if I had finished

school," Evangelista says quietly as he navigates the steep ladder from

his open-air verandah back downstairs into the main mausoleum. "I only

made it to third grade. Maybe I would have had a better job to live

somewhere else." As he knocks on the solid mausoleum walls, he says:

"This is the best house I've lived in; the strongest, safest, with the

best view."

Sent in by R.M. Cables